Open Your Ears

Or, Why You Should Let the Wrong One In

When bad things happened, I thought about otoplasty.

Mom said wait til you’re 18, when you’ll be old enough to understand what it means. At 18, I had other things to think about, and I’ve gone this long, so I let my ears be. And then I went even longer, thinking and doing nothing about it, and decades from now, I still won’t have grown into them, because cartilage continuously expands while the rest of the face loses volume. That’s how nature works, the fucker.

By the time I moved to New York in 2014, I was finally wearing full-exposure ponytails (by choice) in front of select groups: roommates, friends or partners of at least one year, and strangers. I was hot off a surprise, you-can’t-write-this-shit career as a model in Japan, but I never let myself read into it; so many average-anywhere-else foreigners stumble into the same hole. But it did mean I couldn’t hide as easily, and while some hair and makeup artists cooed over, or better, said nothing of my ears, just as many concealed them, and the takeaway was really just, the world has seen them, no running now.

The most remarkable thing about moving to a new place is the freedom to reinvent yourself, to purge what restrained you and adopt what you’d hadn’t had the guts to try. And if anyone looks at you crooked on the other side of your growth spurt, “I just got back from half a decade abroad” will explain every off-putting shift in you character away. Five years later, in my mid-20s, I was teenaged-looking thanks to a combination of Japaneseness, cartoon features and prepubescent choir boy fashion sense, and I was no longer a writer. I was an actor, and my ears were less timid and bigger than ever.

Sometime in the fall, within my first month of living in New York, I was passing time between auditions in one of hundreds of Dunkin’ Donuts’ in central Manhattan. In those early days, and that day specifically, auditions were as late as 6pm, and then 9pm, because everyone involved had a job during the day that made them money. I didn’t request to be seen for the 9pm so much as I received an email in all lowercase from a mysterious address and was so eager (desperate) to work I could rationalize a day or two doing anything for a meal and reel footage.

The Dunkin was two floors, two registers below and seating up top. A cozy Dunkin. There were five of us upstairs: a European-looking tourist couple at a table just up the stairs and against the wall, a mid-40s swarthy gent in the first counter table along the rim opposite them, and on the other end of the landing, a fresh-faced white guy sat two seats away from where I was parked in a corner, bent over myself drawing. I paid little attention to who came up and when, but this was the orientation of the room during the event.

Behind me, a man’s gruffled (gruff and muffled, of a specific enough timbre to fuse adjectives) voice asks for five dollars. “No cash,” is what follows, coming from the swarthy fellow along the rim.

“Can I have a cigarette?”

“Don’t smoke.”

Rude, I think. The brusqueness. Also, don’t come this way, I beg you.

The gruffled-voice man is intimidating. Size, dress, coloring, mien; broad and tall, leather, red, stony. I hear him ask again, five dollars, cigarette.

No.

I notice his fists are clenched, and his knuckles are the only patch of skin that isn’t flushed— they’re white. To the couple at a table along the wall, he asks again:

“Can I have five dollars?” Pause. “Can I have a cigarette?”

He hovers there, waiting for one of them to flinch.

“Can I have five dollars? Cigarette?”

The couple look at each other. They talk to each other quietly, but loudly enough for the room to feel it, in a foreign language. I speak a foreign language, too, crosses my mind. Their banter is universal, the hoarseness of you do it, no you do it, the shrug of make it stop, eye-rolling. The flushed-but-for-white-knuckles man waits patiently for them to bicker; he needs a yes/no answer.

“Ehhh…”

“Five dollars.”

One at a time now. An exaggerated shrug from the man, so helpless to understand.

“Cigarette.”

The same half of the couple shrugs again and then picks up his five dollar coffee and sucks it through the Pez-sized mouth hole. That’s tourist for No.

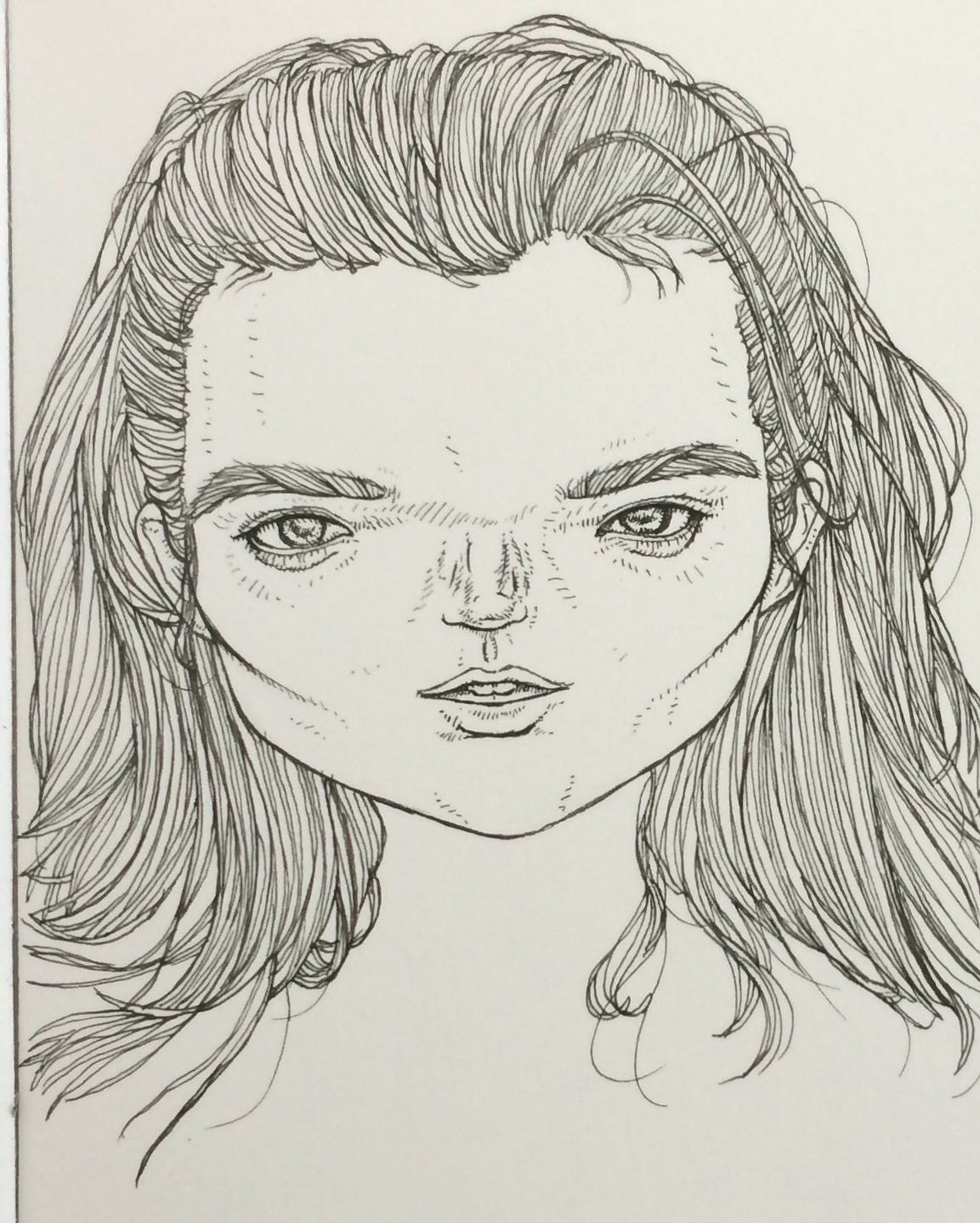

I’m still hunched over myself, finessing a portrait of a girl with alien features on a 3x5 postcard. This was a thing I did, had been doing for three or four years already: between auditions, post up in cafe and draw girls that don’t exist in pen on textured paper. There was a year I held myself to at least one portrait a day, all of which I stuffed into three binders I’ve carted around ten years of New York apartments.

I hear the loops of stiff, major coffee-chain carpet pry apart and stick, and my shoulders growing warm—

“Five dollars.” He’s not asking anymore.

The boy in the corner has decided to ignore him. He faces the wall, engaging himself with its texture. I catch the moment when he realizes he’s turned away from all of his stuff, but can’t turn back; his left arm gracelessly pads the counter and finds his backpack, inching it into his body. If I move slow enough, he can’t see me, or something.

My turn. I turn toward the mass and I smile. I believe a smile can solve anything.

“Give me five dollars.”

A laugh sometimes helps. In this case it does nothing, so I try a new tact:

“So you want five dollars?” I sound like Jerry Seinfeld. It’s a stupid move, but I won’t realize this for at least ten more minutes. “I have five dollars, but I also need the five dollars. You see, I just moved here, and I haven’t made any money yet, and I need every bit of money that I have.”

Nothing. I expect him to ask me again for money, but he doesn’t. As far as I can recall he hasn’t looked at me, only at the floor, or the legs of my high chair. Maybe he’s done here. I go back to drawing.

“Five dollars.”

“Okay. Like I said, I need this money, I worked for it. I’m not opposed to giving it to you, but maybe we could do an exchange for it.”

The peaks of his knuckles marble and go white. His eyes have moved up to my chest—not my boobs so much as my sternum. He’s assessing how hard he will have to hit me for it to shatter, maybe.

“You could sing me a song.” I smile. “Or tell me a joke!” I’m beaming now, I’ve done it!

The man is more brick than flesh, rigid—his whole body is one power lifter’s thigh muscle. The skin around his knuckle creases is peeling back, unable to hold the meat of his fingers. I am putting so much more energy into this than he is. He won’t sing me a song. He won’t tell me a joke.

Back to drawing.

I’m creating the shape of the girl’s face, which is always the hardest part for me, to make it symmetrical; I like it stately but not too masculine. I have a tendency of going too boxy on the left and soft on the right so she only has one jawbone or is turned to the side (see above), but I can’t change perspective because the eyes are already there, and the nose, the mouth, it’s all established. But now it’s considerably harder as I have a shadow, my own shadow, obscuring the lines, and I can’t move out of my own way. I don’t want the guy to think I’m penetrable. Ten, twenty more seconds and he’ll go away. Be strong.

“Knock knock.”

I move my eyes but not my head, to confirm, yes, the guy with the fists is still there, it was him, he is telling a joke. “Who’s there?”

He’s thinking. Maybe. He forgot? He’s not saying anything.

“You were telling a joke just now, weren’t you?” I’ve never hung out with someone this long who hasn’t looked at my face even once. I’m not even sure what he’s looking at, not at my thighs but toward them. “I asked who’s there, so how’s the rest of it go?”

I believe so heartily he will finish the joke I am already rehearsing my response. “Oh! Haha, I like that one.” Or, “Oh wow, I didn’t see it going that way!” but the more time passes, the more hope I—

“A priest and a rabbi walk into a bar.”

“Okay! There we go!” shoots out of my mouth, as if he is a kid with a ball and I am his dad. “And then what happens?”

He tightens, untightens his fists. I say this not to dramatize the interaction so much as state a fact. He is tense, I can’t say why. That isn’t my problem, it doesn’t affect me.

“A priest and a rabbi walk into a bar, and then—”

“You missed it.”

Did I? “What? I missed what?”

“You missed the punchline.”

“Oh, I did?” No I didn’t. “I’m so sorry, can you say it again?”

He shrugs. It conveys a looseness in his shoulders that feels promising to me.

“Please tell me again.”

“Five dollars.”

“I feel like it’s only fair if I get the whole joke.”

“I told you, you missed it.” The way he says you like that, so emphatically, I wonder if he hasn’t also submitted to our parent-child dynamic.

“Okay. I’m sorry I missed it. But a deal’s a deal.” He’s not going to give up. I have to think of something else. “Okay. How about, you say one nice thing. About anything. It can be about me, or about this city, or about this Dunkin Donuts, anything you want.”

How long will we be here, I think. How will he get me this time.

It doesn’t take him long to answer. And he still doesn’t look at me. But with no inflection whatsoever, no feeling about it at all, he says to me, matter-of-factly, “I like your ears.”

All the blood in my body explodes into my face. I am flattered beyond sanity. Radiant. I giggle, I think—did I giggle? I don’t know, I’m beside myself. I explain to him why I’m so moved by his answer, why it was the perfect thing, and it feels important to let him see my joy. He has given me that. He has done me a service.

I reach into my bag and scrounge through an unraveling coin purse for five dollars, and I hand him the bill. The actual exchange of paper from hand to hand is a thing I can’t imagine now, I can’t see past his fists. But he takes it. And then he asks for a cigarette.

“Remember how much work it was to get this far??” Now I’m George Costanza.

“Cigarette.”

I’ve quit smoking by now, I’m not “a smoker,” but I have cigarettes on me. The opportunist in me couldn’t leave Japan without stuffing a carton from duty free into my suitcase on the way out; if I sold them for five bucks over the purchase price, they would still be cheaper than New York’s after taxes. He can’t know that, but he reads it on my face: I have what you want.

I am no different from the others. I have been conned. I broke him for but a second, and I am no different from the rest of the uncaring lot. I stuff my hand in my bag and pry a cigarette out of the pack. As I hand it to him, I’m suddenly aware of the rest of the room. They’re thinking, ew, smokers.

As I start to turn back toward my work, he doesn’t move. He’s not leaving. Alright, I roll my head, turning into him, ready to reason, but before I can say anything, as it’s clear to both of us now I’ll give him anything he wants, he looks at me, and then he points his cigarette toward the window. “Come smoke with me.”

A soft flash of panic strums my chest. Don’t do it. Just say no, you don’t have any more. Tell him you’re a one a day smoker at best, and you like to save it for when you’re alone, at home, in the dark, under stars, with wine, feeling homesick. But I can’t say no. I didn’t come back to say no. We’re not hiding anymore. He likes my ears. The thing that lowered my value, my dateability, the thing I still hear friends’ voices taunting me over, ostracizing me for.

I leave everything behind; not much here beside a pen and twisted self portraits. I follow the man down the stairs. I follow him out the front door. I follow him around the corner to a dark, narrow street, and I take a step toward him. An arm’s reach from his mouth, I am lighting his cigarette. In the shadows behind him, I can make out the wrinkles of a sweatshirt moving toward us with some haste. There’s a stiffness in the figure’s gait that makes me think he could pounce.

I don’t like this ending. The guy who flattered me, by such dumb chance, couldn’t also plot to hurt me. And when would he have called his friend forward? I know where my friend’s hands have been for the last ten minutes.

I go to light my own cigarette. As I hunch down, a body passes through the light I’m under and lands at my side, opposite my new friend; the wrinkles match. It’s a young guy, skinny, his backpack twice the size of his torso. He looks at me like he knows me. I don’t know him.

“You want a cigarette?”

He laughs and his voice cracks. “I was just…” he squeaks, pointing up and back, at the black panes of glass of the Dunkin Donuts, toward where my art and my wallet still sit. He looks scared, in over his head. He’s never done this before. Okay, I think. I’ve tamed one, I can tame him, too. But then he becomes bold, he steps toward me, and as he moves in to whisper at me, he drops the straps of the backpack he’d been clutching like a life raft and I see just how young and soft and white he is. Slowly, with feeling, “I just wanted to make sure you were okay.”

How dare he. The guy who ten minutes ago pretended my friend was invisible, “I’m great!” My voice has gone low. “Why wouldn’t I be?”

The boy goes a bit pale and looks between me and the man, the man and me, two gruffled New Yorkers smoking in a piss-filled alley. I feel bad for him. So young, not a wrinkle on his face, and already so devoid of hope.

“Thanks for checking though,” I smile. “That was thoughtful of you.” And then I turn my back.

I don’t know whether he sees this next part, because I never check on him again, but I hope he does. The marbled-fists guy, all leather, a dope addict, a mobster, UFC fighter, don’t know don’t care—he opens his mouth, and he begins to sing.

“There she goes a-just a-walkin down the street, singin’—”

And his hands fan open. I see his palms for the first time, exposed to the air, butter-colored but warming up, a bloom of blood, and his fingers are in their fullest expression, telling me, this is where you come in. I have a brake that triggers itself in moments like this, a self-conscious paralysis or just plain stubbornness that insists it’s not safe here, they haven’t earned it, don’t give yourself away, but for one of the first times in my memory, I ignore it. As soon as I open my mouth and let a melody out, he will have won a piece of me—after all, that’s what the whole negotiation has been about: winning. But it’s worth it. I have to. I want him to win.

“Doo-wah diddy diddy, dum diddy doo.”

I think no more of otoplasty in any way other than how it would have deprived me of my greatest barometer for kindness, and its inverse; my greatest sense, distance hearing; and my identity totally. Also, money, and all the alterations that would have followed after, as one surgery begets another, and how sad to drown in the pursuit of perfection when buoyant joy is just above the surface.

god mitzi this story is incredible

Just beautiful. You went in one person and left another just because of mutual acts of kindness. If only the world could be this way.